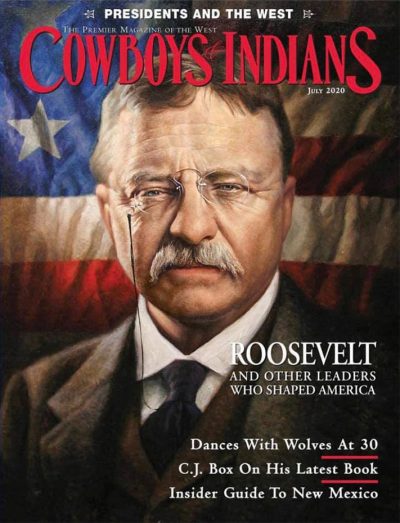

Photo: Diné College English instructor Alysa Landry published an article in the July 2020 edition of Cowboys & Indians. The article is about the early presidents of the U.S. and their policies toward Indigenous peoples.

Diné College English Prof Published in July edition of Cowboys & Indians Magazine

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

June 29, 2020

TSAILE, Ariz.— The first president’s of the U.S. were slaveholders, committed countless acts of violence against Native Americans and have a history of bad politics toward the two groups.

That’s the gist of an article published by Diné College English instructor Alysa Landry in the July edition of Cowboys & Indians magazine. Landry, a former journalist at the Navajo Times and Farmington Daily-Times, picks apart the political policies of presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Franklin and Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, Harry Truman and Richard Nixon.

“In this counternarrative, the presidents who did the most to build the West often committed the most egregious acts against Native Americans,” Landry writes. “Likewise, presidents who consistently rank among history’s worst sometimes did the most for their Indigenous constituents.”

Thomas Jefferson: Landry writes of the devastating effects westward expansion had on America’s Indigenous peoples. Although he never pretended the West was empty — once referring to it as “the crowded wilderness” — Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the U.S. and a slaveholder, nonetheless believed that “Indian Country belonged in white hands.”

Jefferson sent four groups of explorers on western expeditions, including Lewis and Clark. Lewis and Clark was the U.S. expedition that crossed the newly acquired expedition to the western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson also oversaw 33 treaties with tribes — often after driving them into debt and forcing them to give up acreage to pay their bills.

Abraham Lincoln: In 1862, Lincoln pushed Congress to adopt the Homestead Act, the Morrill Act, and the Pacific Railroad Act, each of which transferred large tracts of Indigenous land to corporate or settler interests. With these land grabs, the federal government broke multiple treaties with Indian nations. Under Lincoln’s direction, the Army slaughtered Cheyenne and Arapaho people at Sand Creek, Colorado, imprisoned nearly 10,000 Navajo and Apache men, women and children at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, and publicly hanged 38 Dakota warriors in Minnesota in what remains the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

Calvin Coolidge: On June 2, 1924, Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted automatic citizenship to “all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States.” Also known as the Snyder Act, the bill sought to reward Indians for service to their country while also assimilating them into mainstream American society.

Theodore Roosevelt: In Roosevelt’s 1905 inaugural parade, six Indian chiefs in headdresses on horseback — including the famed warriors Quanah Parker (Comanche) and Geronimo (Apache) — rode through the streets of Washington, D.C. Though the president applauded and doffed his hat as they passed by, it was an era of tension between settlers and Native Americans over resources, a period when boarding schools for Native children intended to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” Landry writes.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt: A cousin to Theodore Roosevelt, FDR introduced his New Deal in 1933, he also established the Public Works Administration (PWA) and pumped billions of dollars into the construction of large-scale projects like dams, bridges, airports, hospitals, and schools.

The PWA stabilized the economy and fortified America with concrete and steel. It also displaced thousands of Native Americans and destroyed their cultural histories or livelihoods, references Landry from scholar and author (As Long As Grass Grows) Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes). This was especially true in the Pacific Northwest, where the government flooded Indigenous homelands to make room for dams.

Ulysses Grant: Grant referred to Indians as “wards of the nation” and advocated for their assimilation into white culture. Grant’s solution to the “Indian problem” was to relocate them to reservations. Only then, he believed, could white settlers and Indian nations live in peace, Landry writes. “No matter what ought to be the relations between such settlements and the aborigines, the fact is that they do not harmonize well, and one or the other has to give way in the end,” he told Congress in December 1869. “I see no substitute for such a system, except in placing all the Indians on large reservations, as rapidly as it can be done, and giving them absolute protection there.”

Harry Truman: Philleo Nash, who served as commissioner of Indian Affairs under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, did a series of interviews in the late 1960s. “At the end of the Truman administration, the Indian people were worse off than they were at the beginning,” Nash said in 1967. Truman’s solution was “to wipe out the reservations and scatter the Indians and then there won’t be Indian tribes, Indian cultures, or Indian individuals.”

Richard Milhous Nixon: Nixon is best known for being the only U.S. president to resign from office, but the politician forever linked to the Watergate scandal also revolutionized federal Indian policy. In 1970, Nixon delivered a landmark address about Indian affairs to Congress. He presented a new policy of “self-determination without termination.”

One of Nixon’s greatest contributions to American Indians, however, came after he left office. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, signed in January 1975, officially reversed Indian termination and authorized government agencies to work directly with tribes. Championed by Nixon, the act was designed to “provide maximum Indian participation in the government and education of the Indian people.”

CONTACT US

Marie R. Etsitty Nez

Vice President of External Affairs

marienez@dinecollege.edu

928-724-6985

George Joe, M.A., M.Ed, Director Of Marketing and Communications

grjoe@dinecollege.edu

928-724-6695

Bernie Dotson, Public Relations Officer

bdotson@dinecollege.edu

928-724-6697

Scott Tom, Graphic Design and Digital Media Specialist

shtom@dinecollege.edu

928-724-6698

Jazzmine D. Martinez, Marketing Assistant

jdmartinez@dinecollege.edu

928-724-6694